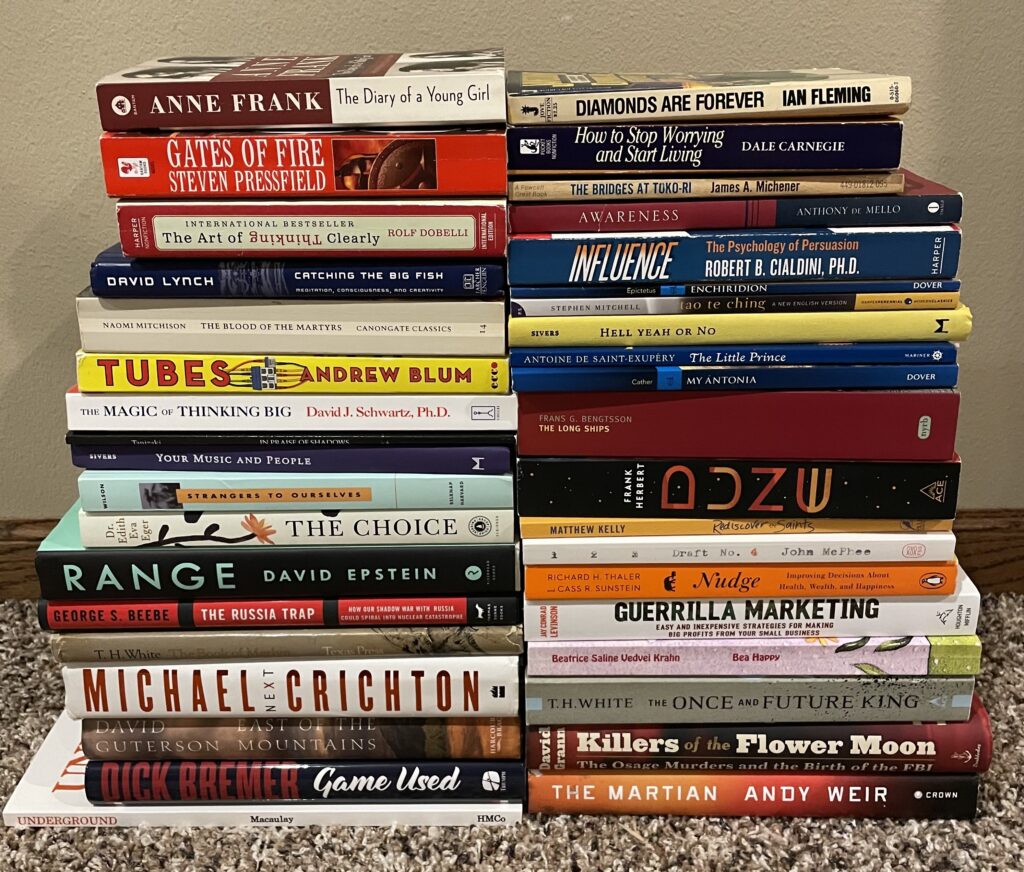

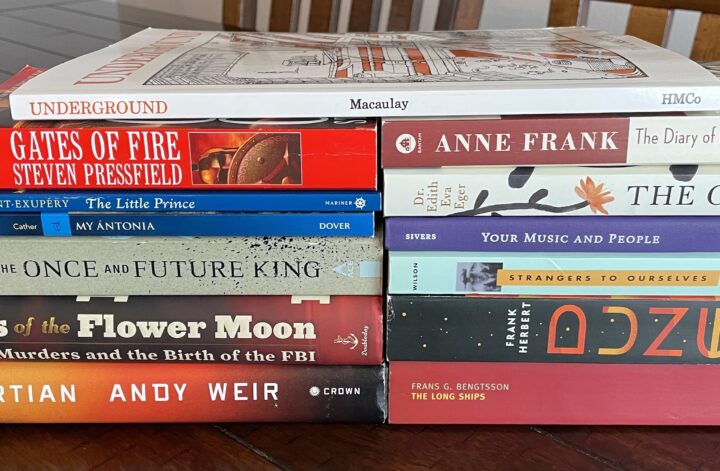

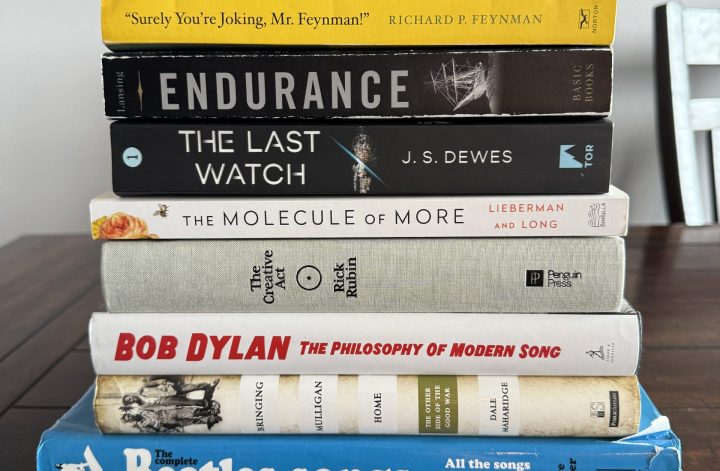

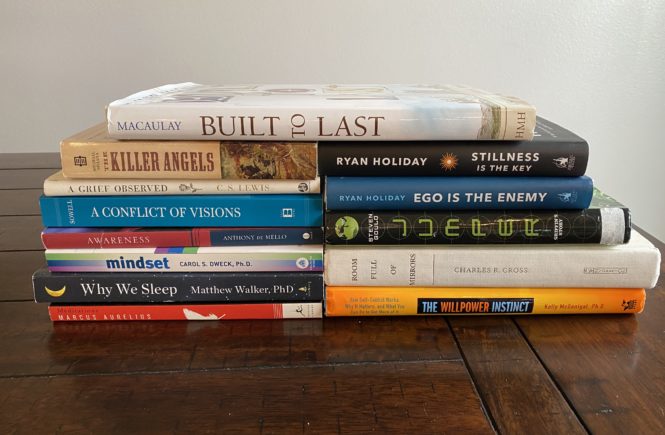

I was hoping to make it through 26 books this year. Then the pandemic hit, and I ended up making it through 46…

Here were my favorites:

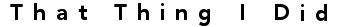

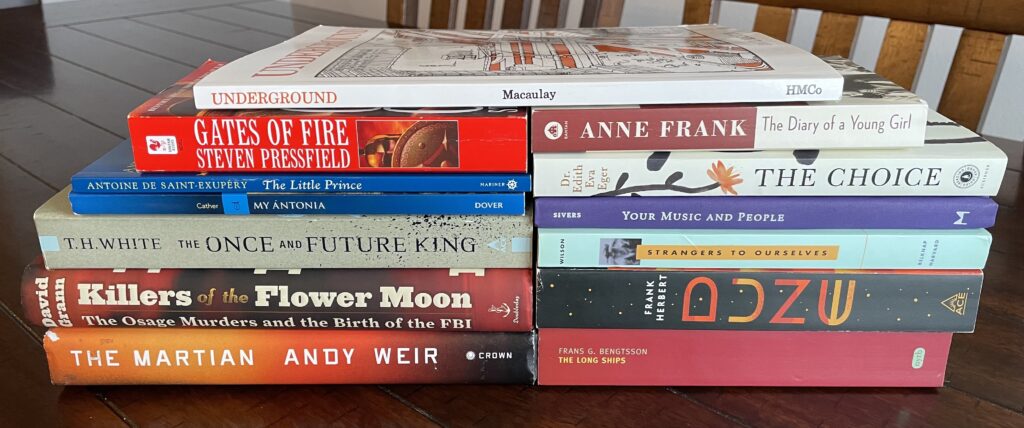

The Choice by Dr. Edith Eva Eger – My favorite from this year. It’s another memoir of an Auschwitz survivor—similar to Man’s Search for Meaning, but I found her philosophical takeaways even better. I also enjoyed The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank, which I’m embarrassed to say I hadn’t read before this year.

Favorite line: To be passive is to let others decide for you. To be aggressive is to decide for others. To be assertive is to decide for yourself. And to trust that there’s enough, that you are enough.

The Martian by Andy Weir – Better than the movie, if you can believe it. I couldn’t put it down. I also read Frank Herbert’s Dune in anticipation of the upcoming movie. I’m planning to read the rest of the Dune series in 2021.

Unreasonable Success and How To Achieve It by Richard Koch – This a new one out by Koch, who also wrote The 80/20 Principle. Koch identifies 20 of the most successful figures in history and then distills their success into nine attitudes and strategies. It’s like reading 20 biographies in one.

Intuition is not random. The more you are an expert in a narrow field, and have deep wells of knowledge and experience in it; the more you think about it, clearly, and with curiosity, the better your hunches will be. Intuition is not the opposite of knowledge – it’s adjacent to it, underpinned by it, the extension of it.

Strangers to Ourselves: Discovering the Adaptive Unconscious by Timothy D. Wilson – Recommended as deeper reading in Koch’s book above, Wilson reviews psychological studies that lay out the “adaptive unconscious”—a set of pervasive, sophisticated mental processes that size up our worlds, set goals, and initiate action, all while we are consciously thinking about something else. It’s similar to Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow but more applicable IMHO. Both provide insight into how our conscious and unconscious thinking can create cognitive biases.

Think about it: we take in 11,000,000 pieces of information a second, but can process only 40 of them consciously. What happens to the other 10,999,960? It would be terribly wasteful to design a system with such incredible sensory acuity but very little capacity to use the incoming information. Fortunately, we do make use of a great deal of this information outside of conscious awareness.

The Long Ships by Frans G. Bengtsson – Michael Lewis recommended this book on a podcast, calling it a comical novel written by a Viking historian. It’s a great hero’s story that also provides a view of what life might have been like a thousand years ago for half of my ancestors. Red Orm’s funny hero’s journey was similar to Lancelot’s in T.H. White’s The Once and Future King, which I also enjoyed this year.

But sometimes he was visited by evil dreams, and then he would become so agitated in his sleep that Ylva would wake him to ask whether the night mare was riding him, or whether there was any trouble on his mind.

My Àntonia by Willa Cather – Another historical fiction, recommended by my friend, Amy Fredregill. The poetic novel details a Bohemian immigrant’s life homesteading in southern Nebraska. I’ll be reading more Willa Cather.

The pale, cold light of the winter sunset did not beautify—it was like the light of truth itself. When the smoky clouds hung low in the west and the red sun went down behind them, leaving a pink flush on the snowy roofs and the blue drifts, then the wind sprang up bitter song, as if it said: “This is reality, whether you like it or not. All those frivolities of summer, the light and shadow, the living mask of green that trembled over everything, they were lies, and this is what was underneath. This is the truth.” It was as if we were being punished for loving the loveliness of summer.

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann – Historical nonfiction documenting the murder of Osage Indians in Oklahoma in the 1920s. The author uncovers gruesome practices in which outsiders would swindle tribal members out of the cash from their mineral rights. The book reads like a whodunit that culminates in the FBI’s first successful high-profile case.

The Little Prince by Antoine De Saint-Exupéry – This is meant to be a children’s book but contains some deep spiritual and allegorical content. The story follows a boy as he leaves his small planet and learns about adult behavior.

“They weren’t satisfied, where they were?” Asked the little prince. “No one is ever satisfied where he is,” the switchman said.

Your Music and People by Derek Sivers – A list of concise marketing advice for musicians, but it could all be generalized for any business. Sivers is a minimalist and total nonconformist, and his short, self-published book is extremely dense. I plan to read it again in 2021.

Gates of Fire by Steven Pressfield – This is a fictional retelling of the Battle of Thermopylae, and the basis for the movie 300. Great way to learn about Greek culture from 2500 years ago.

“I swear to you, mates, so numerous were the multitudes of bowmen that when they fired their volleys, the mass of arrows blocked out the sun!”…To his disappointment Dienekes regarded him with a cool, almost bored detachment. “Good,” he said. “Then we’ll have our battle in the shade.”

Underground by David Macaulay – Similar to his other greats, The Way Things Work and Built to Last, Macaulay uses simple illustrations and explanations to describe a topic most of us know little about. In this case, he covers the basics of two underground systems: foundations and utilities.